Florian Ebner wrote the foreword for our publication "Double Take". He is a curator of photography and a lecturer. Currently Chief Curator of the Department of Photography at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, he was curator of the German Pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale in 2015, Head of the Photography Collection at the Museum Folkwang, Essen, and Director of the Museum für Photographie, Braunschweig, before that.

GLORIOUS MAQUETTES

BY FLORIAN EBNER

The significance that some images have in our collective memory is shown in the afterlife that they lead. Major historical images that are specific landmarks in the history of photography not only live on in endless reproductions and publications, but also persist secondarily in the form of parody or homage.

Thus ‘Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima’, an award-winning picture taken by Joe Rosenthal on 23 February 1945, has a unique place as an emblem of America’s victory in the Pacific War: reproduced millions of times over, the motif has been used for a postage stamp and a major war memorial; it has also featured in many books and films, and has been the subject of conjecture about the authenticity of the moment. Yet gradually this image has begun to take on a life of its own. There have been numerous paraphrases and parodies of the celebrated group of figures that have served both commercial and political purposes. A key example is the scene, captured on camera, of New York firefighters hoisting the Stars and Stripes on the smoking rubble of the World Trade Center: the photographer’s recording of the moment evokes Rosenthal’s precursor, a connection that has been analysed in detail by photography curator Clément Chéroux.

Images like ‘Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima’ are often called photographic icons. They derive their authenticity from the photographer’s eyewitness account, and their potency stems from the reduction of complex historical circumstances to an event rendered as a picture. In some cases, only a single image has persisted through the endless process of reproduction to become firmly inscribed in our collective memory as a representation of wars and catastrophes, the charisma of a film star, or the quality of an artist.

The power of icons has consistently fascinated and perplexed artists. It has also challenged them to offer a different narrative rendering of these famous photographs. For example, there are numerous approaches based on the idea of re-enactment, of restaging the event for the camera with the help of actors. Other artistic methods use Photoshop to intervene in the image, editing in a detail or even deleting significant elements in the picture. What these strategies have in common is that they play with the mental image of the icons in the mind of the viewer.

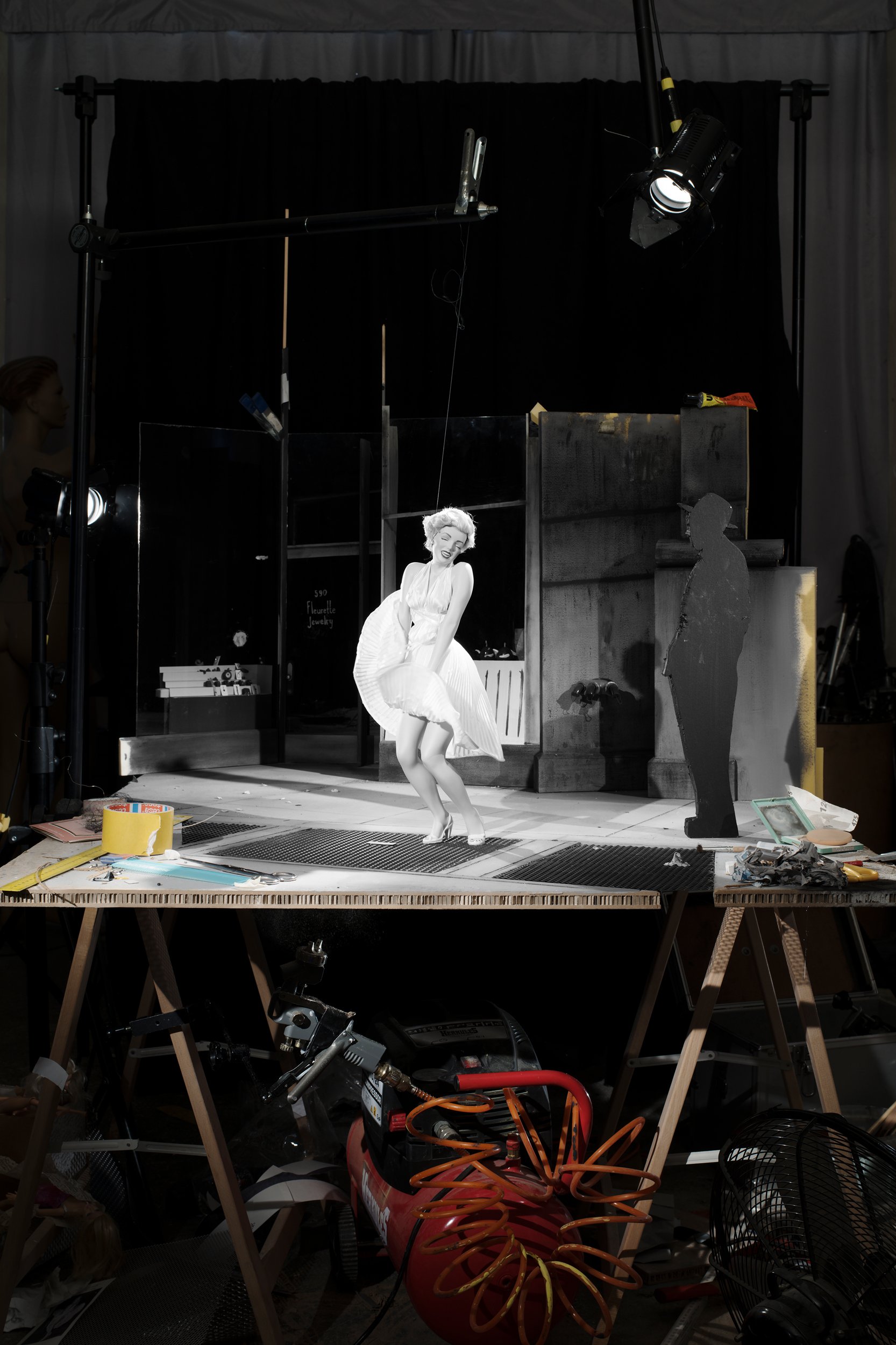

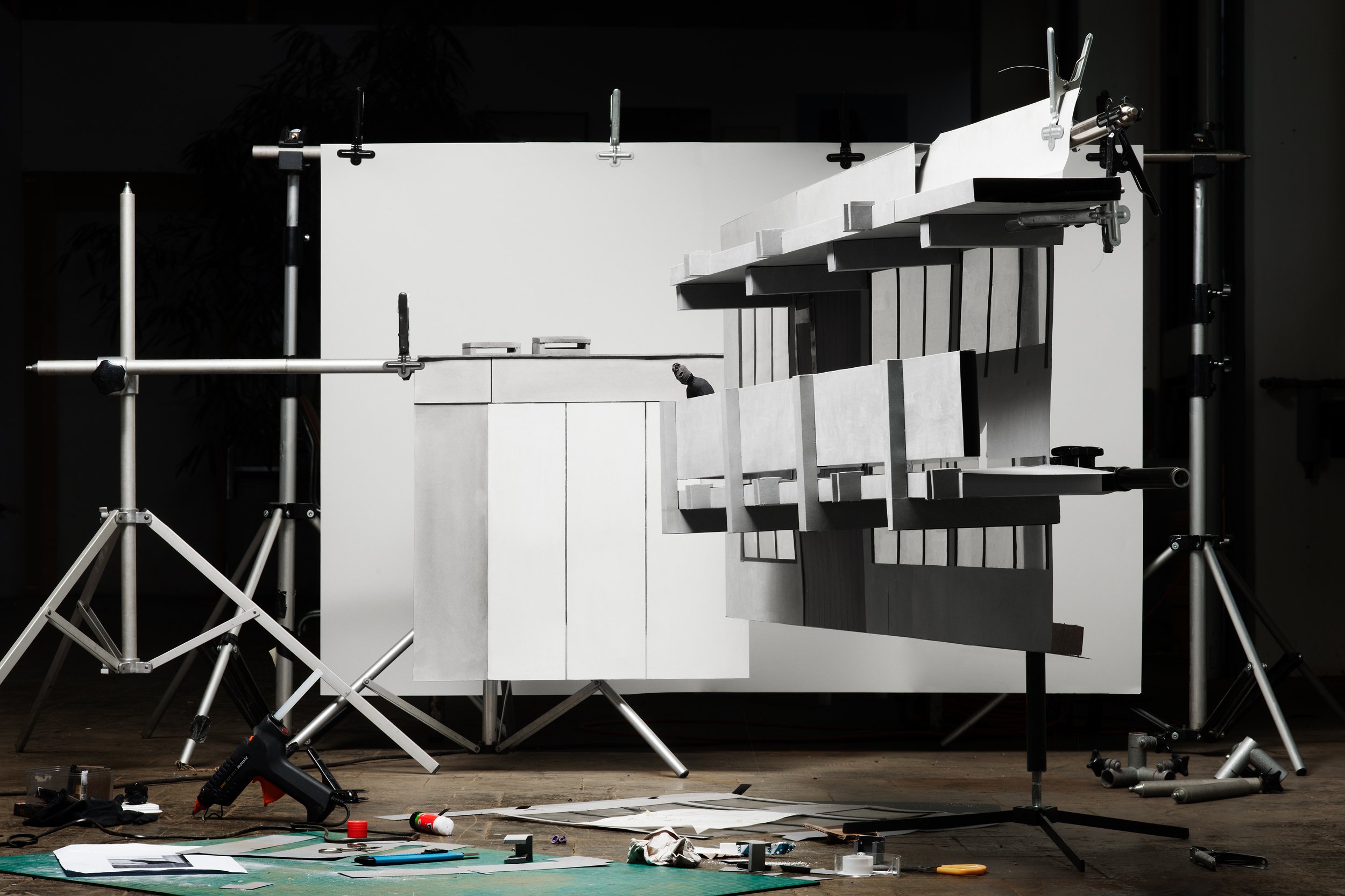

Jojakim Cortis and Adrian Sonderegger take a different approach. Rather than focusing on the action and the moment, they emphasize the space and the construction of the image. They restore the depth of the three-dimensional space to the two-dimensional surface of the photographic icons, returning the instant in the past that has become enshrined in history to the constructed, present-moment reality of their studio. These compositions do not set out to conceal their constructedness but provocatively turn it outward. Moreover, the studio continues the world captured in the photograph beyond the boundaries of the image: the spotlight in Cortis and Sonderegger’s studio becomes the spotlight in New York’s Palladium in 1979, when Paul Simonon smashed his guitar to pieces.

All of a sudden the original edges of the icons emerge as the crops and trims that have hitherto prevented us from seeing that all these great images might in reality have been artifices, moments constructed for the camera. The footprint of the first man on the moon was nothing more than an imprint in a sandbox in a photo studio. But isn’t that what we’ve always thought?

Cortis and Sonderegger’s re-enactments thus draw on the compositional power of these images, perpetuating or amplifying it, as when, for example, the outstretched arms of the American Olympic athletes giving the Black Panther salute are allowed to bleed into the dark studio backdrop, which seems to extend upwards to infinity.

At first sight, the two photographers’ ‘Making of…’ might seem somewhat audacious when compared with the great historical models, yet the pair take it upon themselves to recreate the settings from nearly two centuries of photographic history, conjuring them time and again out of nothing. They achieve this with an almost boyish delight, revelling in the bricolage that is a characteristic feature of certain modernist works (one is reminded, for example, of another famous Swiss artist duo, Fischli/Weiss).

Nonetheless, the seemingly irreverent chaos surrounding Cortis and Sonderegger’s studio compositions is also a precise and profound comment. Their interpretation of ‘Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima’ encounters its heroic forebear with the necessary ironic distance. Thus the plateau at the top of the mountain is raised up from the studio floor by standing it on two ordinary plastic crates. In compositional terms, the glue gun inversely mirrors the diagonal of the flagpole, which the grey-clad group of figures, matching the original black-and-white, is about to raise aloft. It is no coincidence that another American flag lies on the studio floor: the now-famous picture actually captured the hoisting of a second, larger flag.

This series by Jojakim Cortis and Adrian Sonderegger sends a major blast of fresh air through the eternal circulation of icons. Rather than appropriating the photographs for political purposes, they inject them with their brand of visual humour, as they invite us to take a close look at the composition of their images. It is a playful reminder that the great icons of history do not simply appear out of nowhere but are also informed by a constructive will: ‘You don’t take a photograph, you make it!’ (Alfredo Jaar, appropriating a sentence attributed to Ansel Adams). This form of homage is not the worst thing that can happen to these illustrious images.